| Stufen Wie jede Blüte welkt und jede Jugend Dem Alter weicht, blüht jede Lebensstufe, Blüht jede Weisheit auch und jede Tugend, Zu ihrer Zeit und darf nicht ewig dauern. Es muss das Herz bei jedem Lebsensrufe Bereit zum Abschied sein und Neubeginne, Um sich in Tapferkeit und ohne Trauern In andre, neue Bindungen zu geben. Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne, Der uns beschützt und der uns hilft, zu leben. Wir sollen heiter Raum um Raum durchstreiten, An keinem wie an einer Heimat hängen Der Weltgeist will nicht fesseln uns und engen, Er will uns Stuf‘ um Stufe heben, weiten. Kaum sind wir heimisch einem Lebenskreise Und traulich eingewohnt, so droht Erschlaffen; Nur wer bereit zu Aufbruch ist und Reise, Mag lähmender Gewöhnung sich entraffen. Es wird vielleicht auch noch die Todesstunde Uns neuen Räumen jung entgegen senden, Des Lebens Ruf an uns wird niemals enden... Wohlan denn, Herz, nimm Abschied und gesunde! Hermann Hesse 1941 | Life’s Stages Just as every blossom wilts and every youth Gives way to age, so too does every stage of life, Every wisdom too, and every virtue blossom When due in time and may not endure forever. At each of every call of life, one’s heart Must be prepared to part and start anew, In order ably and bravely and free of sorrow To give itself to other new commitments. And each beginning harbors its own magic, That shields us and that helps us on with life. Let us with joy exhaust one sphere upon another, And to none of them as to a homeland cling, The cosmic spirit is not upon binding and limiting intent, It wants to lift from stage to stage and broaden us. Hardly at home are we in any circle of life, Cozily settled, before we threaten to go limp; He alone who is ready to leave and to journey forth, Can the paralyzing force of habit escape. It is quite possible that even the hour of death Us will youthful further to new realms, Life’s call to us will never end… Well then heart, take leave and fare you well. Translation by Joseph Mileck June 2007 |

A Life Well Lived

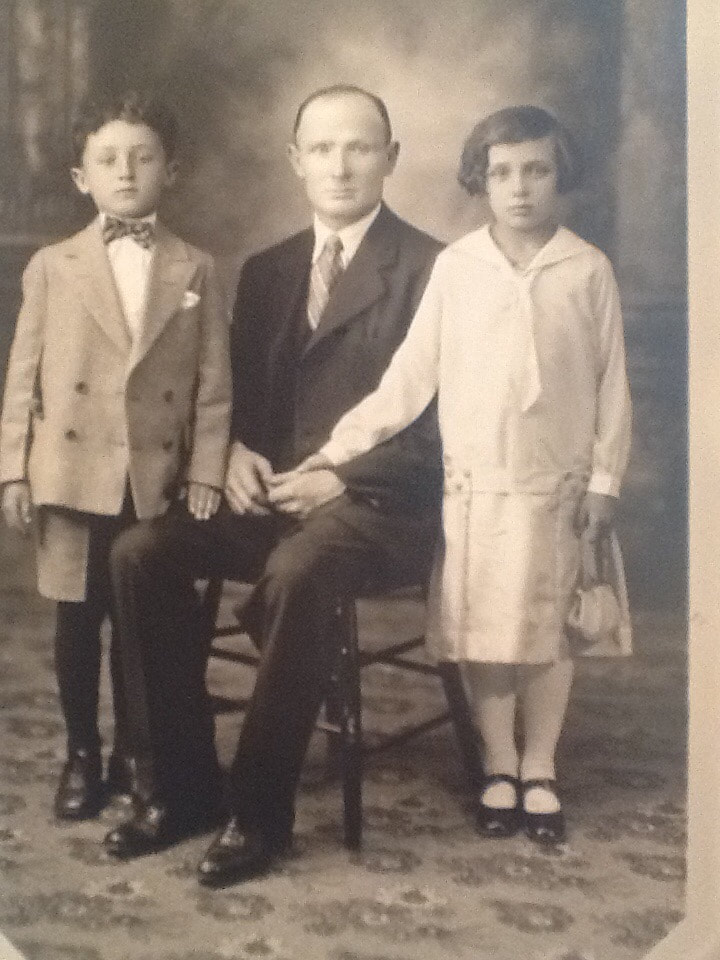

Joseph Mileck was born in a small German speaking village called Sanktmartin in Rumania in 1922. The village was a peaceful one, where life proceeded in an organized predictable pattern honed over hundreds of years. Joseph was a happy, energetic child, with an older sister, two hard-working parents, and loving grandparents nearby. Farming was the main occupation and the Catholic church the center of activities and the yearly calendar.

In 1926, the family left for Canada. Joseph's father had left earlier, working on the prairies of Canada. He soon learned of opportunities in Hamilton, Ontario, working for Dominion Foundry and Steel Company (known affectionately as Dofasco). He found work there and sent for his family. Joseph, his sister Mary and his mother travelled to Hamburg, Germany to catch the ship to Halifax. Joseph had no memory of that trip.

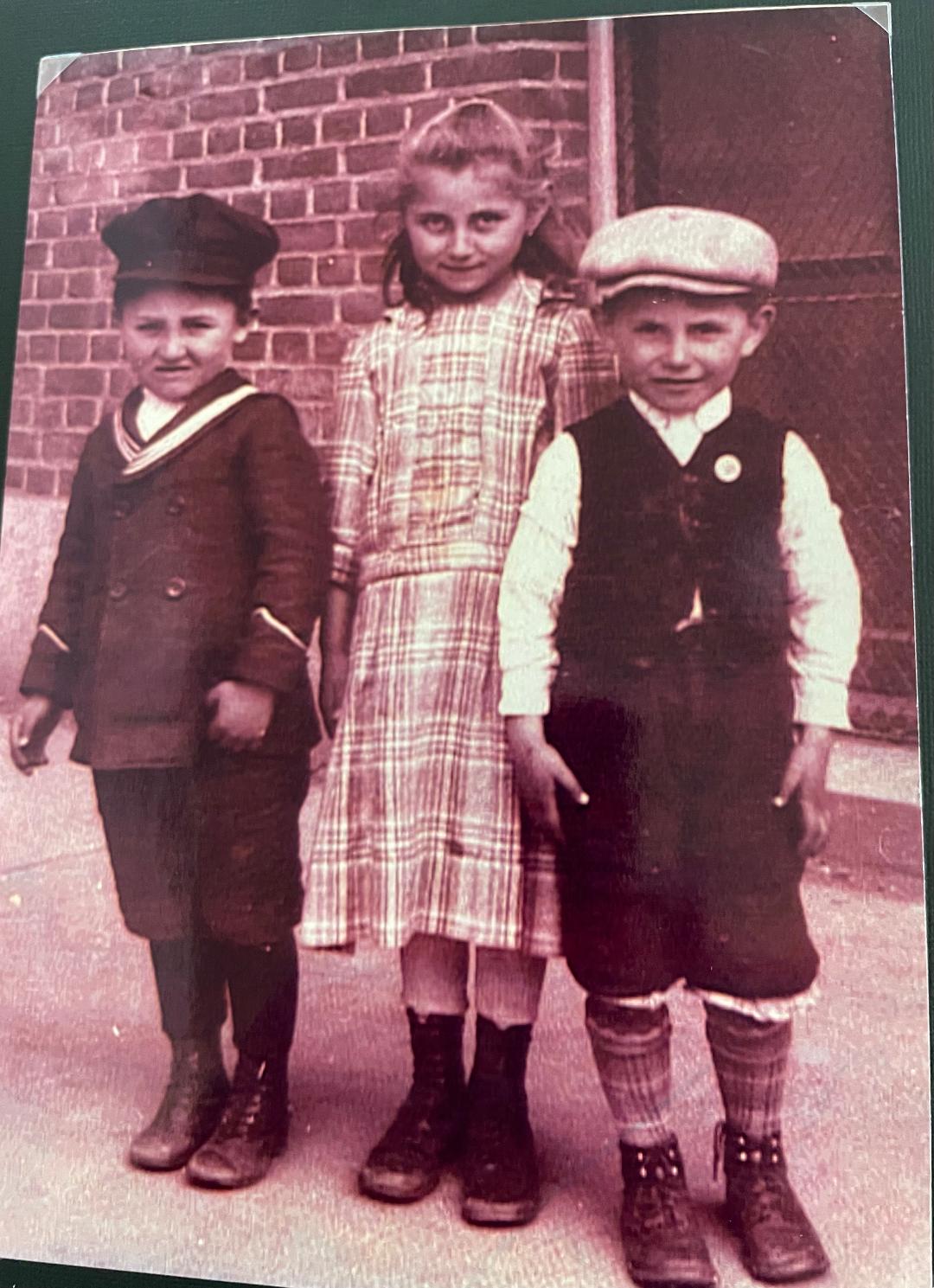

Joseph had many friends in the neighborhood and soon learned a few words in Hungarian, Ukrainian, and Polish. He picked up English in school from the teachers and thus acquired good pronunciation and vocabulary. Swearing and other salty language was done in the East European languages of his friends. It was a happy life for the children.

In 1930, Joseph and Mary were sent back to Sanktmartin to live with their grandparents. The Depression meant his father might lose his job and the parents planned to follow the children back. Joe remembered being very sad riding on the train to Halifax. The next memory was of arriving in Arad, Rumania, where their grandfather greeted them in the wagon drawn by spirited black horses. Joe remembered jumping off the wagon to pick the mulberries that grew along the side of the road.

Thus began the happiest year of Joseph’s life. He and his sister Mary were known as the Amerikaner. They were special. They didn’t have to go to school since they didn’t know Rumanian, the language used in school. Their grandparents were indulgent. Joseph never really said what his sister did that year. Perhaps as a girl and older, she was put to work. Did she enjoy the year as much as her brother did? I never found out. She did seem to have fond memories of Samktmartin. Joseph spent his days playing. His parents sent—one wonders how—his scooter from Canada and that made him everyone’s friend of course. His grandfather made him a whip and set him to work herding the pigs. Well, that was disastrous and he never had to do it again. He was free to explore, to play with his friends, to tag along after his grandfather, to join in wherever he wished.He even had silkworms as pets for a while. He enjoyed the structured rhythm of village life. The women worked in the house, cooking, cleaning, helping each other, while the men tended the fields, the vineyard, and the livestock. Sunday was for church, the bell ringing to call the entire village together for worship and socialization. It was an honor for a boy to be chosen to ring the bell. Saturday night was for music and dances. There was the yearly calendar too, driven by the church, but allowing for merriment as well. Christmas, Easter, wedding and funerals were times to congregate, for music, for timeless rituals. The cemetery was all important as well, a symbol of the continuity of the village. When in 1990, the Germans began to leave St. Martin, they all regretted most leaving their departed ones in the cemetery and they appointed someone who was staying to tend to the graves. Emigrants to Germany regularly visited St. Martin when it was politically feasible and raised money to keep the church and cemetery in good shape.

Back home, Joseph was now behind in school. He had forgotten all his English and had had no schooling for a year. He remembered his friends all gathering around him to welcome him home and the only word he could say was “sure.” He started school and worked diligently to catch up. He was not one to sit back on his heels. This drive to catch up and to succeed was to remain with him for the rest of his life. His sister was behind too and older, and she developed a dislike for school, dropping out at age 14. But Joseph persevered and was soon at the top of his class .He loved to read and checked books out from the mobile library that visited the school each week .He liked the stories of the Royal Mounties in the North. He relearned English and modelled his language on that of his mostly British teachers. In the summers, Joseph worked on the farms, picking fruit. He enjoyed this work, was competitive and excelled at it, and never felt exploited. He was proud that at one point he was earning more money per week than was his father.

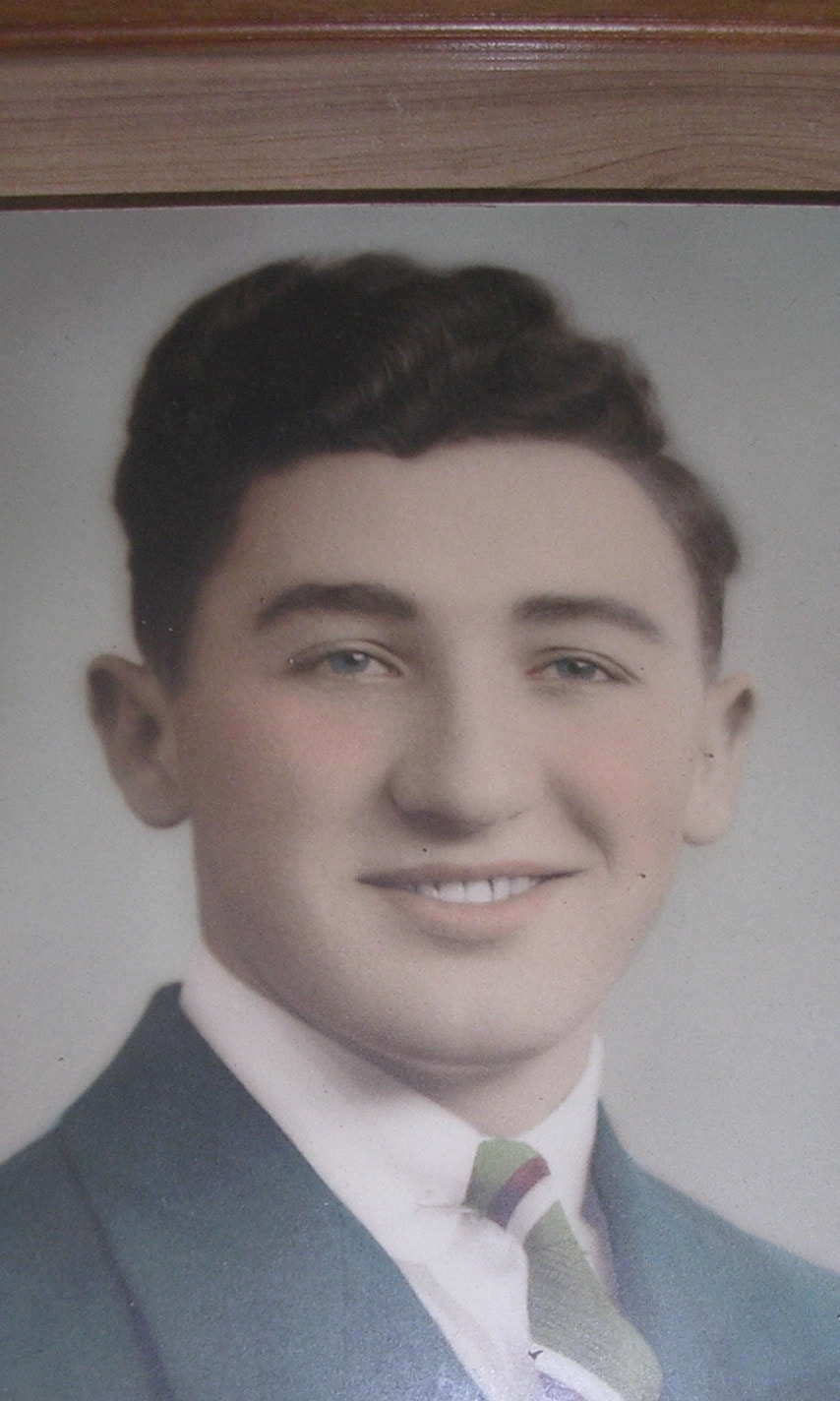

Joseph graduated from elementary school after the eighth grade. Most of his friends went on to the Technical High School. His sister had entered the Commercial High School. But Joe was determined to follow the mostly British students to Delta Collegiate. After a few weeks, he found it too daunting, and he tucked in his tail and went to Tech. But this didn’t please him, so he tried Commercial. Typing was boring. So several weeks into the school year, he headed back to the Collegiate. Here he had to scramble to catch up, but he did so and soon loved the challenges of this academic high school.

The tone was set. For years, Joe would enter school a few weeks late because he was working on the fruit and then tobacco farms ,and he would have to hurry to catch up. But he did so and excelled. He studied French, German, and Latin, as well as English, Math, History and the Sciences. He played basketball for a while and played violin in the school orchestra .He studied hard and was at the top of his class.

Joseph was awarded top honors each of his final three years of high school, and at the end was offered a four year tuition scholarship by the province of Ontario to attend the local McMaster University in 1941. He had planned to go to Normal School and become an elementary school teacher but the scholarship persuaded him to go one step further.

That McMaster was not far from Joseph’s neighborhood meant he could live at home and take the streetcar to school.. He got his own attic bedroom now where he could study in peace. Just as In high school, he excelled at his studies. Joseph liked the rather formal British atmosphere at the university, where women wore dresses and stockings and men wore suits and ties. The professors and seniors wore robes. There was a daily chapel which most attended and which Joseph enjoyed. Most of the faculty was British and he continued to model his behavior and language after them. The college was also small, with only 700 students, so that the faculty and students got to know each other well.There was little time for socialization.. Joseph no longer had time for sports and violin. But he enjoyed his school work and continued to excel.

The summers continued to be for manual labor. The summer after he graduated high school and each subsequent summer, Joseph worked at the Dominion Foundry and Steel Company, where his father and many other relatives and neighbors worked. He did have some time for other pursuits as well. All physical fit males were enrolled in the ROTC as well and took military classes two afternoons a week. In the summer, they had several weeks in camp. This appeared to have been more fun than toil and was conveniently located at Niagara by the Lake, a quaint little town by the touristy Niagara Falls. One incident that always remained in Joseph’s mind was war related. He was working night shift. One day, he was awakened by two Royal Mounties standing at his bedside. They insisted on searching his room. They found and took the family’s correspondence with family in St. Martin and took the little bit of American money that Joseph had from working on a cruise ship on the lakes in the summer. Indignant, Joseph went down to the central office and demanded the letters back. He was told that he had better shut up and leave or they would jail him. Joseph’s father did listen to German radio and he did subscribe to an American German language newspaper, but he had nothing to do with Germany other than the language. He had been born and raised in St. Martin, as had his wife and the children, and their forefathers back to the 1700’s.

His first year at Harvard was difficult. He was away from home, in unfamiliar surroundings, rooming in the homes of strangers and eating in a cafeteria. The university was large and impersonal. For more than a month, Joseph was homesick. But he soon made friends, got to know the professors, and rose to the challenge of a rigorous graduate school curriculum. He studied Gothic, Old High and Middle High German, and brushed up his Latin and French. Literature study spanned all eras, from Old High German through the 2oth Century.

By the end of his first year, Joseph was well acclimated. He met the academic challenges, received a Master of Arts and was accepted into the Doctoral program. A teaching fellowship would help pay for his housing and tuition. He continued to study hard but was now more confident. He also found time for some socialization He found housing in graduate dorms and made friends, he would visit the undergraduate houses for meals, and he even dated a bit. I heard stories about his dates with he daughter of a steel magnate. They sang opera together in the car, chaperoned by a family member, of course. He spent a memorable weekend on Cape Cod, went sightseeing in New York City and visited the sights of Boston. On Sundays, he visited churches of various religions, enjoying the ceremony and the music, but unimpressed by the dogmas and sermons.

But study came first. His days began at 9 am and ended at 10 pm. his. He taught two elementary German courses three mornings a week and took his own classes in the afternoon. Evenings were spent studying and writing papers in Widener library until it closed at 10pm. On at least one occasion he was locked in because he failed to heed the closing signal..

Joseph’s last two years at Harvard were the most enjoyable. No longer required to take courses, he focussed on his dissertation on Hermann Hesse, deciding to write on Steppenwolf.

He submitted and defended the thesis in 1950 and was awarded a PhD. that June. The timing was propitious. Post war, student enrollment at colleges and universities had grown rapidly and there was a shortage of professors. Joseph received offers from Brown and Northwestern Universities, but always one to accept a challenge, he chose instead to accept the offer from University of California at Berkeley

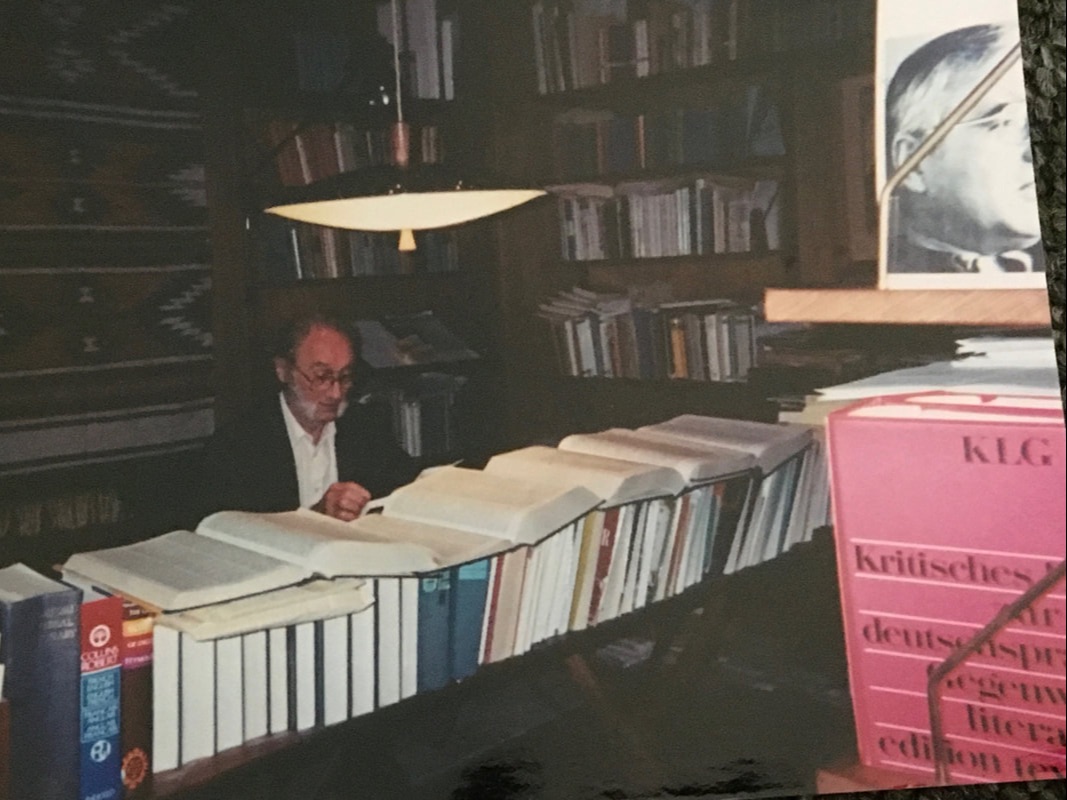

In the end, Joseph became one of several internationally recognized Hermann Hesse scholars. He then wrote a shorter work : Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. This book was popular not only among scholars, earning praise even from a rival, but among the general reading population, and is still in print today,

During the course of his career, Joseph also performed his duty to serve on committees or in various assignments.He was in charge of the teaching assistants for a number of years then undergraduate advisor then graduate advisor. He chaired the German Department for five years , was assistant dean In the College of Letters and Science for three years and the University’s ombudsperson for four years. This latter seemed to be a favorite position. He liked students, and liked helping them, while remaining fair-minded.

All of these duties required time. Joseph was no stranger to long hours and hard work, so he applied himself continued his long hours, working fifty or more hours a week. In the summer, he did his research and prepared courses. Despite the long hours, Joseph found time to meet a Danish woman, whom he married in 1951. They bought a house in the Berkeley hills and soon had three children. This required a larger house, so they bought three lots in the Berkeley hills for a thousand dollars each and had a house built to their specifications. Now he and his wife, a doctoral student, had to meet the demands of their scholarly work as well as take care of a family and home.

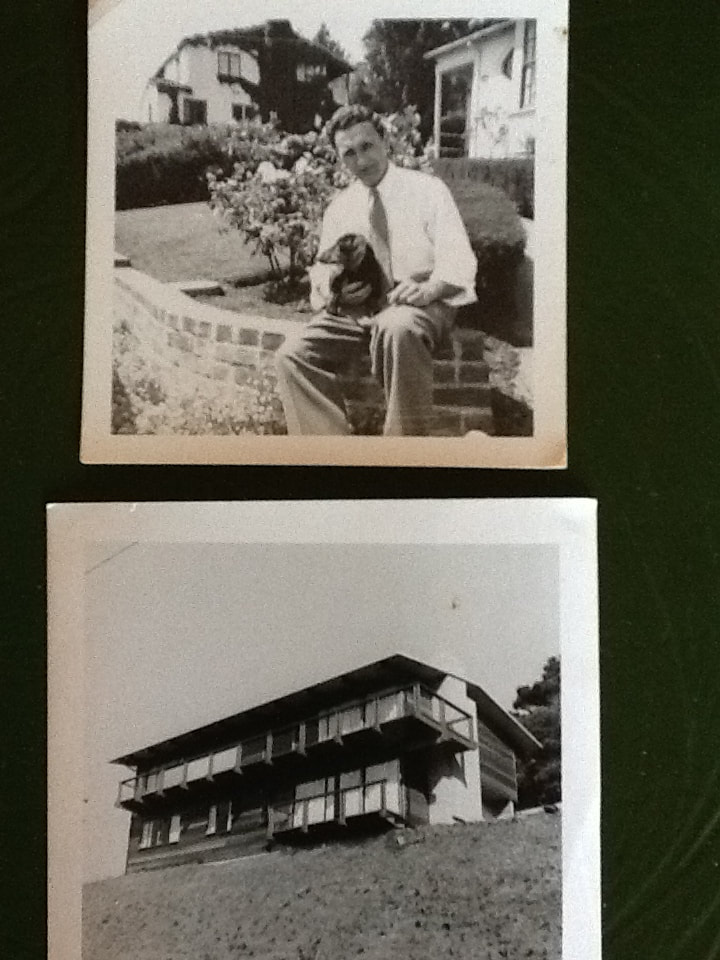

| top photo: the wedding reception at the Claremont Hotel in 1951 top right: the family, kids Martin, Paul and Anne-Marie left: Joseph with his first dog Rudolph at the first house. left bottom: the newly constructed Sterling Ave house. Joseph landscaped the three lots belonging to the house by himself, buying at least thirty trees to cover the wild oat covered lots. |

I will leave the next part to Joseph’s own words:

But neither my wife (a doctoral candidate in the German Department and a Danish instructor in the Scandinavian Department) nor I were inclined to rein in our careers enough to meet the demands of home and growing family. For a number of years, continuous domestic help and childcare seemed to make possible both family life and careers. However, while careers flourished, family life was clearly more casual co-existence than warm interaction. Parents had too little time for each other and children were too often left to their own devices. That my wife was manic-depressive and suffered a breakdown in the sixties and again in the seventies, did not help matters. By the seventies, it was obvious that marriage had become too great a burden for my wife. She left home, husband and children in 1975 and filed for divorce the following year. Divorce was a godsend, a painful relief for all concerned. In the years following, my erstwhile wife fared better on her own, and I, in turn, became a more interactive father.

Left to our own devices, my children and I became quite domesticated. A house had to be kept in order, meals had to be cooked, and a garden and hill had to be tended to. We all had our duties and all went reasonably well. More time for family meant less time for profession, but this, fortunately, had no negative impact on my teaching, and my scholarly output, while slowed, continued satisfactorily until I finally retired in 1991.

Retirement (in Joseph’s words)

Before retirement, University salary and good real-estate investment returns had made for a financially carefree and materially comfortable life, and had made it possible to see my children through college and to assist my ex-wife monetarily. After retirement, pension, social security and savings, together with investment and stock-market returns guaranteed a financially secure old age, and enabled me to assist my adult children and ailing ex-wife, and to see my three grandchildren through college. Being of help rather than being in need of help has been gratifying, but the freedom, in retirement, to preoccupy myself with whatever and whenever I please, has been absolutely exhilarating.

In the nineties, long-time academic interests shifted very quickly to a more mundane and more personal engrossment. Over the years, I had maintained contact with my Rumanian birthplace, had visited Sanktmartin numerous times, and had carried on an active correspondence with relatives and friends. I had also acquainted myself with the political, economic and general social lot of Sanktmartin in a Rumania become communist after the Second World War. After several more investigative returns to Rumania in the early nineties, I edited a collection of articles that focussed on Sanktmartin's lot in a communist Rumania. The book was published in 1993. A subsequent preoccupation with the eighteenth-century German dialect spoken in Sanktmartin culminated in a book-length linguistic study published in 1997. I then edited a collection of articles that dealt with the mass emigration of Sanktmartiner shortly after the assassination of President Ceausescu in 1989. Rumania's Germans were finally allowed to leave the country unharassed and without recourse to bribery, and they left en masse. A German Sanktmartin became a Rumanian Sin Martin.

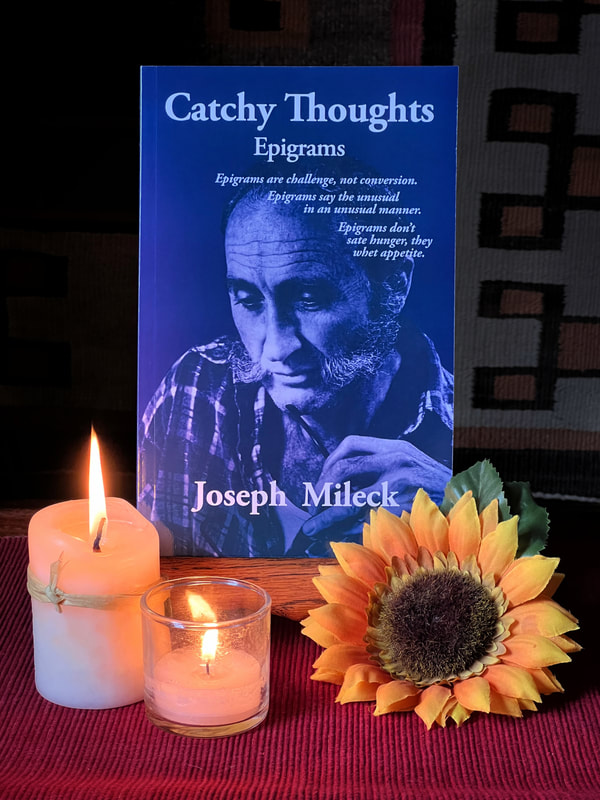

Having paid my respects to my birthplace, I then turned my attention to yet another long-time interest, to poetry. My love of poetry began in high school, I started my own poeticizing while at McMaster, and then for decades and but for the occasional poem, the private interest lay fallow for want of time and active interest. Retirement rekindled my interest in poetry. I had written mostly romantic poems; I now began to put existential reflections and socio-political commentary to verse. Three booklets of rather piquant poems and epigrams appeared in print from 2008 to 2012.

I had become a citizen in 1953, but had for years, for want of interest and time, paid very little attention to the socio-political state of America. It was not until my retirement that America received the serious attention it merited. My preoccupation with its domestic and foreign policies, capitalism and individualism, its materialism and consumerism, and with its imperialism and militarism, found its way into America: An Empire in Disarray (2013), my latest and perhaps last book.(he went on to pen four more books of epigrams)

While the pace of my post-retirement writing differs little from that of my pre-retirement years, the pace of my private life has slowed progressively. I still tend to garden, house and kitchen, but ever more slowly and with less zest. My circle of friends has become painfully small, but children and grandchildren have remained a comforting compensation. Mary, my treasured bosom companion of the past thirty-five years and Píccola, my playful dachshund of the past four years--the last of my four-legged friends--have been and continue to be a constant joyful presence. But for the removal of tonsils, thyroid and cataracts, I have never really been sick, and do hope that I continue to be blessed with good health for yet another few years, for I plan to tarry yet a little while.

All in all, life was good and I was fortunate. Pain and sorrow were more than balanced by well-being and joy, and struggle had its ample rewards. I was blessed with good genes and fate was kind. And when my time comes, I hope to leave with thanks upon my lips.

written in 2013

Joseph continued to write epigrams up to the last month of his life. His last book, Catchy Thoughts, was published in time for his hundredth birthday in May of 2022. He filled one more lined paper pad in the ensuing six months, dictating them to me in the last few weeks. He would be sitting there at the dining room table, silent. I would think he was sleeping then he would open his eyes and say “Write.” I would take up a pen and he would dictate an epigram. His mind remained sharp up to the end. But he was more than frustrated with his failing eyesight due to macular degeneration. And just as determined to remain in control of himself. He continued to cook, albeit with my help, he watered the garden but now left the harder work to his son Paul, and he was helping with the housework up to the last year of his life.

He had a few falls, none serious, but became aware that he needed someone else in the house and asked me to move in on Solstice 2020. I did so and we soon established a pattern, two loners who liked to work in their studies, but met for meals and shared household duties. We had always done the grocery shopping together when I visited on the weekends. Now, when Covid hit, I took over all outside errands to protect him from contagion. We continued to do the housework together. Little by little, I took over more of the work, but he was cleaning his own bathroom up to a month before he died. I took over more of the cooking as well, making the recipes he had always liked, but he continued to make his salad with its many ingredients and plenty of olive oil and vinegar. It was when, in the last month, he stopped making and eating salad that I knew the end was near

Joe had for quite a while lost his sense of taste and ate only dutifully, not from pleasure. Then food started to not be tasteless but distasteful. Nothing pleased him. In November of 2022, he spent a few days in the hospital for jaundice. Tests showed three masses in his digestive system. A procedure was performed to clean out the masses but it was clear that this was only a temporary fix. Upon leaving the hospital, he was unsteady on his feet and I could no longer leave his side. I moved my computer upstairs to his study to be within earshot and we enlisted the help of our weekly housekeeper to come every afternoon. He regained his appetite for food briefly and I was cooking real suppers for him again. But after a few weeks, he found all food distasteful again and he would eat only canned soup, jello, and watermelon (yes, one can buy watermelon in November!). Whatever he asked for, he got. Previously, he had developed the habit of spending several hours on his lounge chair outside in the sun, but now the weather turned cold and he could not do so. So he now spent his days either in bed or on the sofa, covered with blankets and with a heating pad against his belly. And his faithful Piccola glued to his side.

But he still dictated epigrams, he still was in charge telling me what to do, and he could walk with a cane and my aid. I would joke that we were going for a promenade.

It was only the last two days , December 21 and 22, that things changed. He could not walk even with aid, he couldn’t eat at all, and he stayed in bed. Piccola’s eyes were clouded with worry and she huddled ever closer. Anne, Joe’s daughter came down, we ordered a hospital bed, his son Paul brought in a wheelchair and we enlisted the aid of hospice, with whom we had contracted just a week earlier.

The night of December 22, Anne stayed the night. Joseph slept more peacefully than he had been doing. He awakened once in the night and was convinced to stay in bed. He fell back asleep and didn’t awaken until 6 am. He died peacefully at 6:15, with Anne and me each holding a hand and Píccola forever at his side.

Joseph Mileck’s ashes were interred on January 6, 2023 at 12 noon at Sunset View Cemetery in El Cerrito, California.

Yours was truly a life well-lived.

"Each life has its trail and each trail has its tale."

"Be someone and do something."

-JM 2022