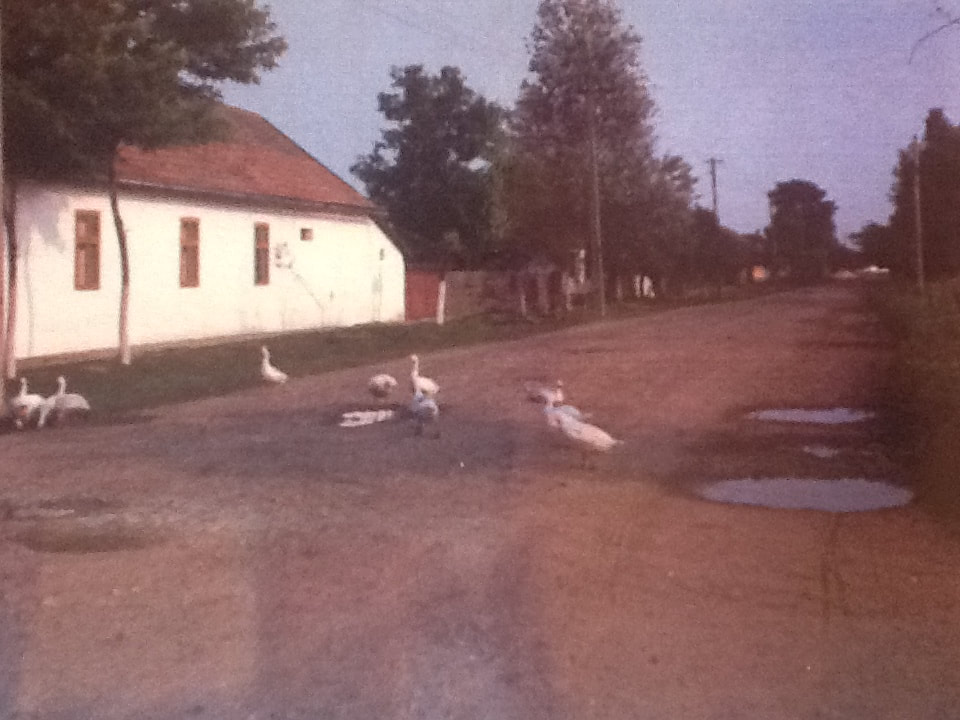

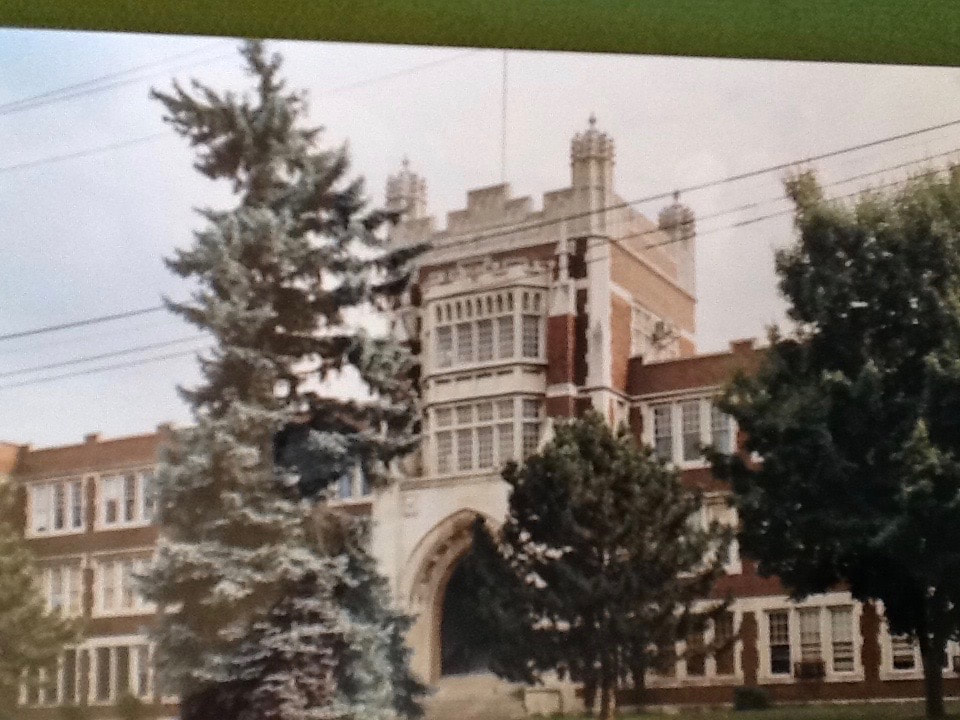

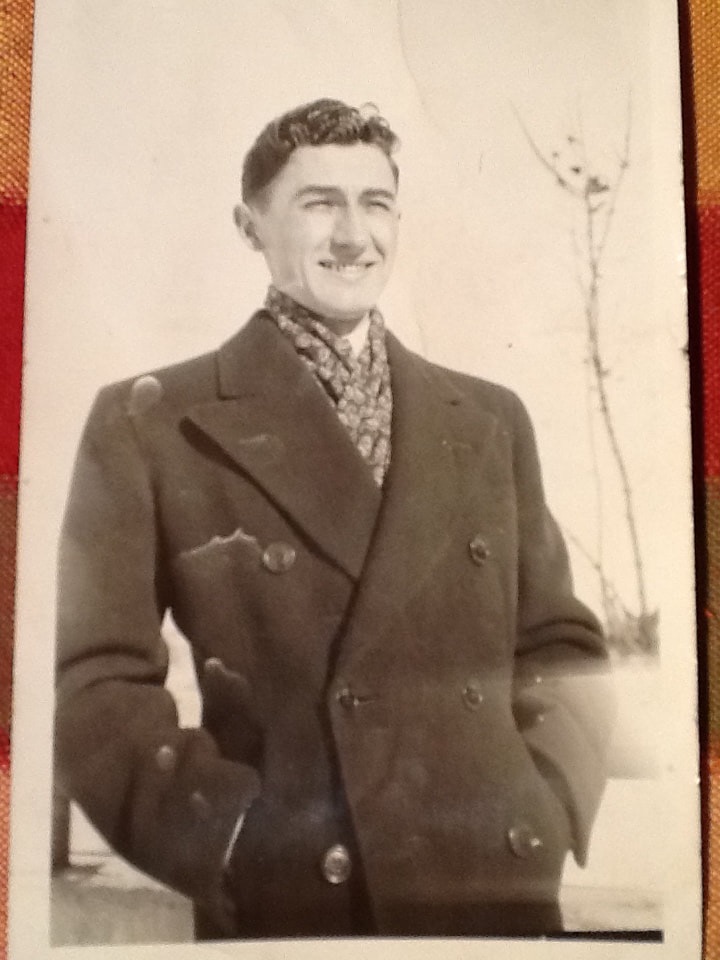

| Early Years I was born long ago and far away. It was in 1922, in a little German peasant village that chanced to germinate in Rumania in the year 1724, the town of Sanktmartin. The many new and widely scattered farm communities were all more or less alike, patterned after the most attractive of Austria’s villages. Each settlement featured a central square flanked by a church, a rectory, an administrative office, and the village elementary school. All streets were broad and straight and bordered by run-off gutters and walkways, and all could be extended to accommodate a growth in population. Each of the settler families was granted close to an acre of land along one of the streets. The houses that lined the streets were all more or less of a kind: one-story elongated adobe structures that housed family, provided a covered space for farm equipment, and stabling for horses and cows. Each house was plastered and whitewashed, and every house had its red tile roof. The large yards, too, varied little: each had its outhouse, manure pile, straw stack, storehouse for fodder corn, chicken roost, pigeon loft, pigpen, vegetable garden, and a draw-well with a large wooden trough for the farm animals. Each village had its own nearby mill and cemetery, and grain fields, vineyards and pasture land surrounded each village. An artesian well in the village square supplied the drinking water, petroleum lamps provided lighting, horse-drawn wagons did all the transporting, and a town crier went daily from street corner to street corner shouting out the latest news and coming events. Each village family was more or less self-sufficient; the fowl and the pigs provided meat, the garden its vegetables, the cows their milk, and the fields their grain. The women cooked, baked, made the family’s clothing and tended to the children, and the men took care of the animals and farmed the fields. The days began at sunrise and ended soon after sunset. The stables had to be cleaned, animals fed and cows milked before breakfast. The menfolk then left on their wagons for the grain fields or vineyards and the children scurried off to school, while the women stayed at home tending to their domestic chores and to the yard. At 8 o’clock, soon after the evening meal, the church bells ran curfew and children had to be off to bed. Adults retired soon thereafter. In the summer of 1926, mother left with me and my slightly older sister, to join her husband in Hamilton, Ontario. Father had left for Canada in 1924, spent two years on a wheat farm in Saskatchewan, then got a better-paying job in a steel plant in Hamilton, and promptly had his family join him. Industrialized Hamilton attracted poor immigrants from almost every country in Europe. The newcomers characteristically moved into the shabby houses clustered around the smoky and noisy spread of factories. Ours was one of those rented homes on a short and muddy dead-end street with railroad tracks and rumbling factory but three short blocks away. Our three bedroom house was shabby, but it did have gas, electricity, running water and a bathroom—luxuries we did not enjoy in Sanktmartin—and it quickly became a comfortable new home for the family. The house also quickly became a home for a steady flow of boarders, singles and couples, and primarily fellow Sanktmartiners. It was a noisy setting with little privacy, but it was also lively and this as a youngster I enjoyed very much. All was well for the family. Father had a steady job in the Dominion Foundry and Steel Company, mother tended to family and boarders and my sister Mary and I began our education at Lloyd George, a relatively new elementary school but a short block away. I was but four years old, but stubbornly insisted on joining my older sister in Kindergarten. The school obliged. | I was a very inquisitive youngster, a good listener, an immigrant child determined to prove to himself and to convince others that he could vie with the best in whatever undertaking, and I also enjoyed applying myself. This blend of tendencies served me well. I was the school’s top student from grade six to grade eight and was one of but two students who qualified for admission to a collegiate, a five-year academic high school. The school year at Lloyd George was not all work and no play. Homework was quite light, and there was ample time for softball and soccer in the spring and autumn, and for sledding and hockey in the winter. I even had time to help father and mother in some of their old peasant autumn practices. Each year a pig was slaughtered and hams and sausages smoked in the backyard; wine was made and barrelled in the cellar, and the cellar shelves had to be filled with countless jars of pickled peppers, cucumbers and beets, of preserved cherries, peaches and pears, of a variety of jams, and of tomato sauce and paste. This was intensive labor, but it was also a learning experience for which I was to remain thankful. That the family became Canadian citizens in late 1931 changed our lives little, if at all. That the family was able in 1936 to leave the ghetto for a lower middle-class neighborhood, transformed our lives. We now lived on the right side of the tracks, in our own house and near a shopping center and not a factory. Mother’s life quickly changed for the better: she no longer had to tend to boarders, enjoyed her first running hot water, her first refrigerator, and particularly her first washing machine. She still had more than enough on her plate of responsibilities, but her decade of drudgery was over. The change in father’s life was less dramatic but no less positive: new eight- rather than ten-hour shifts in the factory, left him less exhausted and with more time for his family and circle of German friends, time for a new German weekly newspaper, and even some time to listen to the evening shortwave broadcasts from Germany on a newly acquired radio. It was also not until my parents lived among Hamilton’s Johnsons, Mackenzies and Hendersons, and not among its immigrant Vasiloffs, Jelinskis and Guyresiks, that they finally began to learn English, the beginning of their slow social integration. My decision to go from an immigrant elementary school to a select academic high school, was as bold and rewarding as was my parents’ decision to leave the ghetto for better possibility. Delta Collegiate was a five-year institution primarily intent upon educating university-bound students. It was located in what was then a choice residential neighborhood, and attracted primarily the sons and daughters of wealthier English, Scotch and Irish families. I was clearly out of my element, and more than just slightly bewildered. In desperation, I fled the scene after but three weeks and enrolled in a Technical High School where most of my boyhood friends had ended. Fortunately or unfortunately, no trade appealed to me, and the Commercial High School I then sampled, left me cold. It was mid-semester before a contrite I was back at Delta, re-admitted by an understanding principal. I now focussed on school, to the exclusion of all else, and thanks to my supportive parents and patient teachers, was, by the end of the year, competing with the best of my classmates. Effort and persistence had again paid off! I continued for two summers to work on fruit farms around Hamilton, and then spent two laborious summers living and working on a tobacco farm some 75 miles from Hamilton (another learning experience). Fortunately, effort and persistence were almost daily rewarded and Hamilton’s McMaster University saw fit to award me a four-year tuition scholarship for my performance in Ontario regional examinations at the end of my fifth year. I had planned to proceed to a Normal School from Delta to become an elementary schoolteacher; McMaster’s scholarship persuaded me to go a step further in academics. |

Laboring in a primitive pre-Second World War steel factory in Hamilton’s hot summer months was sheer torment. The constant din was deafening, the soot-filled air was stifling, and the heart and labor were exhausting. Earplugs were a necessity, salt tablets staved off muscle cramps, and steel-capped boots and steel-laced gloves protected my feet and hands. Shift work did not help matters (7-3, 3-11, 11-7): the factory was as hot during the night as it was during the day, sleep in the heat of day after a night shift was fitful at best, and the weekly change of shifts left my mind and body quite confused. it was a grind, but the income, together with scholarships, made continued study possible.

My four years at McMaster were both rewarding and enjoyable. In 1941, it was still a Baptist college with but forty professors and lecturers and with only some seven hundred students. Everyone at McMaster seemed to have at least a nodding acquaintance with everyone else. On the opening day of the autumn semester, the freshmen gathered in the chapel of the university, were always reminded that they were now young adults, and were expected to dress and deport themselves accordingly. Dress meant suits and ties, and dresses or skirts and stockings. A friendly, British-like formality prevailed. Professors wore their black academic gowns, as did the seniors. And the daily mid-morning chapel service was always well attended by both faculty and students

When it became apparent, at the outset of 1945, that Germany was about to collapse and the war would soon end, I had to make a quick decision. It had been my plan to proceed from McMaster to the Teaching College in Toronto, and from there to highschool teaching. This possibility had lost its attraction. My introduction to the study of literature at McMaster had whetted my appetite for further literary study and study at a good American university could be another exciting adventure.

My first year in Cambridge and at Harvard was the trying test I suspected it might be. Away from home and friends, on my own in unfamiliar surroundings, rooming in the homes of strangers, and eating three meals a day in cafeterias left me decidedly homesick for more than a month. My transition from a tiny and ordinary McMaster to a colossal and world-renowned Harvard was equally discomforting, but only until I knew my professors and their expectations, and until I had struck up a friendship with a number of classmates.

By the end of my first year in America, I felt quite at home both in Cambridge and at Harvard. I had convinced myself that Harvard’s expectations were not beyond me, had received a Master of Arts, was accepted in the German Department’s doctoral program, and was awarded a teaching fellowship. The future was promising and I was content. The following four years were just demanding of time and effort as the first, but they were thankfully free of my first year’s apprehension.

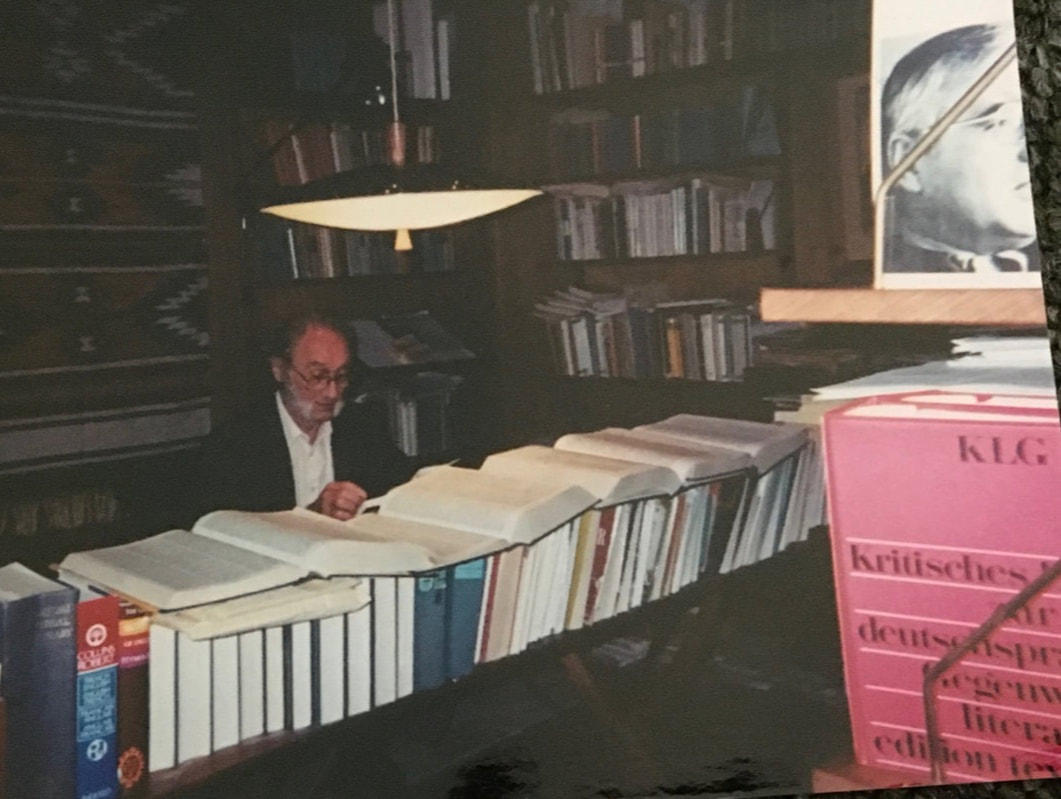

My last two years at Harvard were the happiest of my five. I left private rooms, cafeterias and seclusion for a graduate dormitory, a graduate dining hall and greater interaction with my fellow students. I had completed my course work and was able to devote most of my time to my doctoral dissertation. Hermann Hesse had attracted my attention when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1947. When I read his startlingly innovative novel, Steppenwolf, I knew immediately that he would be the subject of my dissertation. I submitted the dissertation in early 1950, defended it orally shortly thereafter, and was awarded the doctoral degree that June.

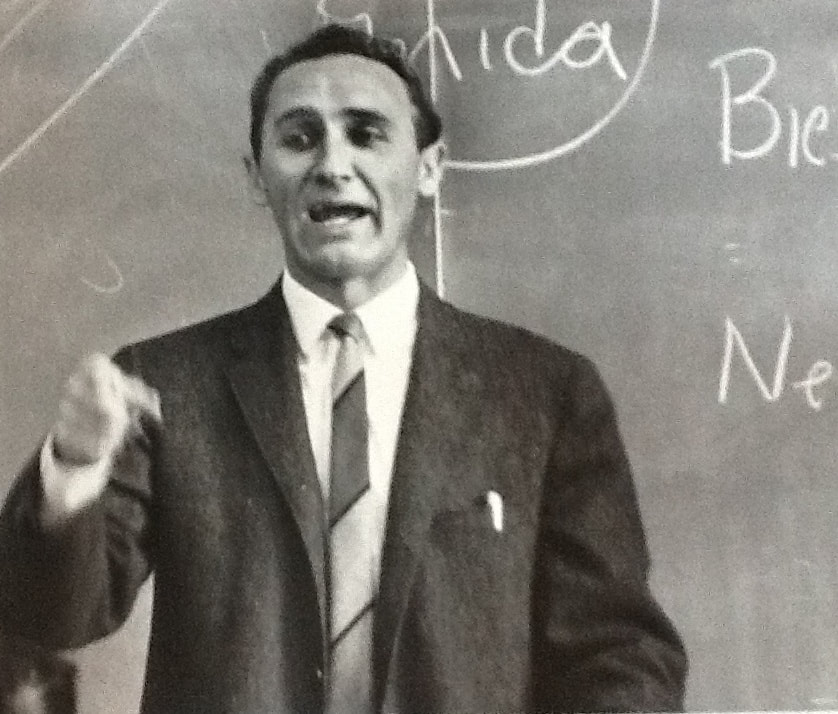

All’s well that ends well! My student trials and tribulations were over and three universities had already offered me an instructorship. In the post Second World War years, student enrollment at colleges and universities burgeoned, faculties had to be expanded, and there was a shortage of Ph.D.s. Doctors of Philosophy had their pick of jobs. I could not have finished my studies at a more appropriate time. Rather than Brown or Northwestern University, I chose the University of California at Berkeley.The salary was acceptable, and the teaching load left ample time for research. Furthermore, California, the land of sunshine and orange groves appealed to me. I have never regretted the decision!

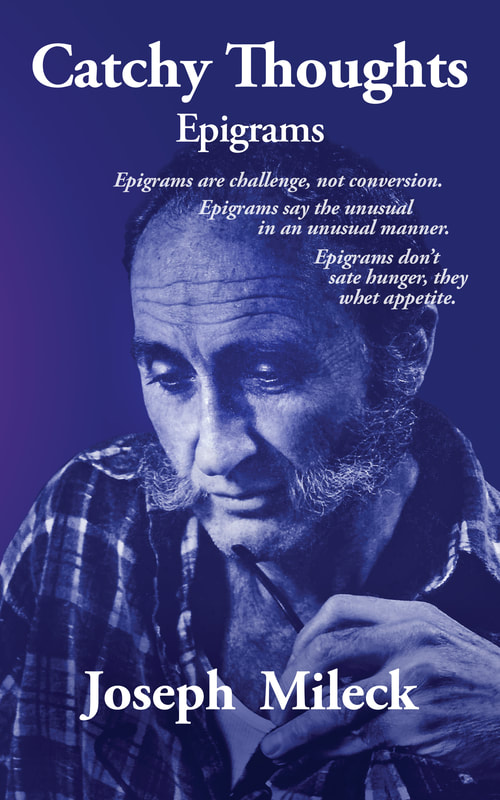

After retirement, he wrote several books about his home town in Roumania and its dialect, then turned to poems and epigrams. His latest book of epigrams was published this year and is available on Amazon: Catchy Thoughts. Indeed a life well lived. And the epigrams just keep coming, albeit a bit more slowly than in the past.

Let the painful past be, and focus on a better present.

Be what you would be, and take the consequences.

Try to be what you would be if you could be.

Too many talk too much and do too little.

It's better not to do it, if you are likely to rue it.

Don't envy or belittle, admire and emulate.

Every epigram is an essay in the making.

When unfettered capitalism is in, democracy is out

Life is a drama for which there are no rehearsals.

To try is to learn, and to learn is to grow.

It is what it is, and not what you would have it be.

Mutual concessions pave the way to a better relationship.

If intent upon resolving a personal problem, don't argue your cause, describe your plight.

Listen, then reflect before you counter argue.

Master your hypersensitivity or it will master you.

To try is to court failure, not to try is failure.

Wisdom is a state of mind, not a mode of thinking or a thought.

Every seed is much in little.

Help silently, before help is requested.

To hide your light is to be left in the dark.

Too much potential is never realized.

To tax where there is poverty, is to seed where there is no soil.

To be selfless is to be faceless.

But for life there would be no death.